Aquatic invasive species have changed the context of public access.

Now try this one: If there is a lake in Minnesota that no one can access, does it provide any benefit?

Two answers surface:

The first is moral, even spiritual. I like the notion that I might discover an unvisited lake and venture into a place that has not yet known the hectic push of modern life. As Edward Abbey said, “Wilderness is not a luxury, but a necessity of the human spirit.”

But the more realistic answer is that a lake no one can access provides no benefit to the public. Public benefit is the point of public policy — the utilitarian effort to do the most good for the most people most of the time.

Access to water resources is a crystal-clear public good. Most of Minnesota’s towns and cities are adjacent to water. Water-related tourism provides over $12.5 billion in revenue. Lake-based recreation is a primary economic engine of greater Minnesota, and lakeshore property is the drivetrain.

ANTHONY SOUFFLÉ • Star Tribune

Keegan Lund, a specialist in aquatic invasive species for the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, held up the shell of a native mussel covered in zebra mussels he found in White Bear Lake.

The average cabin owner spends about $5,000 annually on local goods and services. Cabin owners also pay property taxes. A lot of property taxes. A recent Star Tribune article noted: “In 10 of Minnesota’s 87 counties, [cabin owners] shoulder more than 40% of the residential property tax burden.” In some counties, cabins make up nearly 60% of the tax capacity.

All along, Minnesota’s people — the indigenous peoples, the voyageurs, the settlers, the immigrants and all of us — have enjoyed unfettered access to every water body in the state. With passage of the Dingell-Johnson Act in the 1950s, the federal government created a stream of funds from the federal Treasury to the states to provide for greater access to water resources.

Minnesota receives about $35 million in such federal funds annually, and today it has more than 3,000 public water-access sites. How many thousands of private ramps are out there is unknown.

Open access to lakes and rivers is egalitarian, benefiting all races and classes of Minnesotans. Until recently, no one has questioned the public good of open access to lakes, because there has been no reason to question it. For thousands of years there has been no downside.

Aquatic invasive species (AIS) have changed that.

AIS are an existential threat to lake-based economies and Minnesota’s way of life because they are spread by humans. They are spread, to be precise, by access.

I can hear the bar stool biologists claiming that ducks, turtles and other critters spread invasives. So far there is no scientific evidence that they have. But even more to the point, if AIS were spread by natural means, we would be measuring the spread in terms of centuries, not summers.

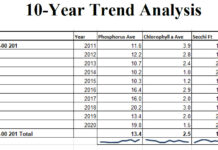

There has been a 160% increase in AIS-infested waters in the past five years, from 402 in 2013 to 1,049 in 2018. That is not turtles.

Among the 181 lakes with DNR carry-in access only, none of them are designated as being infested by zebra mussels. Only four have Eurasian milfoil. Yet many of these lakes lie near infested lakes with waterfowl moving freely among them.

Faced with the rapid spread of destructive aquatic invasive species across Minnesota, it is time to define what “access” means. Is access simply the ability to get into a lake? Or does access mean more — does it mean access to a resource that people want to get into?

Put another way, is providing a boat ramp on a lake so clogged with aquatic invasive species that boating, fishing and swimming are impossible really providing access? Do we have to protect the lake itself if we are to provide access to a resource that supports our economy and way of life and honors our outdoor heritage?

If the utility of a lake drops — if AIS proliferate, the fishing crashes or runoff-generated algae blooms take over, or if water levels rise or fall too much — “access” to the resource we value is undeniably impaired. Our ability to enjoy the resource is diminished. Without access to real recreational opportunities, tax base and business suffers. Schools and other public services collapse.

So with AIS, access is not only the problem but also the public good we must protect. If boat ramps on infested lakes are shut down, the damage to tourism, recreation and way of life would be the same as if the lake were so choked with AIS as to be unusable.

Researchers at the University of Minnesota and the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources are now finding that the combination of spiny water flea and zebra mussels in Mille Lacs are a significant driver of walleye decline in that lake. Do the resulting fishing restrictions and subsequent loss of revenue in Mille Lacs communities represent a loss of effective “access” to the resource? You bet they do, and the financial consequences have been significant.

Bottom line: If we want to protect access to natural resources with the utility we value, we must find and stop the boats, trailers, docks and boat lifts that are carrying these destructive species over public roadways from one lake to another.

The DNR estimates that it would cost about $68 million annually to put an inspector at every Minnesota boat ramp for the duration of open-water season. With some 13,000 lakes and about 900,000 registered watercraft, that estimate might be low.

Fortunately, there are alternative policy models in other places around the U.S. based on mandatory, regionally organized inspection and decontamination services that benefit from economics of scale. Most of the western states use a version of this model.

There are many different programs, all variations on the same theme. Convenient roadside inspection stations are set up at ports of entry and other traffic chokepoints. Boats and equipment are inspected, then tagged as clean. When a boater reaches the destination, half of this tag is put into a lock box at the ramp; the other half goes on the dashboard. Law enforcement officers check these boxes to make sure that all the vehicles at the ramp have complied; they write tickets if they have not.

Some remote access sites have self-inspection. Boaters fill out a checklist of actions they must take. Boaters sign it, declaring that they have complied.

As a result, invasive mussel spread across the western half of the U.S. is much slower than in Minnesota, even though the west has more lakes, more boats and more geography than we do. The Pacific Northwest employs coordinated mandatory regional inspection programs and remains free of invasive mussels.

Fines for an AIS violation in Idaho are $10,000.

Colorado set a goal of 100% inspection before launch in 2008, using mandatory regional roadside Watercraft Inspection and Decontamination (WID) programs. They have intercepted 144 watercraft with live zebra or quagga mussels attached. A number of these infested boats were from Minnesota.

Yet last year, instead of adding new lakes to its infested-waters list, Colorado was able to remove a lake. It remains invasive-mussel-free.

Mandatory roadside inspection before launch seems like a lot of inconvenience just to intercept 144 infested boats a decade. But those boats are the source of spread and represent 144 lakes that might have been infested — along with all the connecting waterways to those lakes.

What would have been the value if we had stopped and decontaminated the boats or water-related equipment that carried zebra mussels and spiny waterflea into Lake Mille Lacs?

In 2012, Minnesota passed a law giving the DNR the authority to use a mandatory centralized inspection protocol, and the agency has employed some temporary roadside stations. In 2018, Wright County passed an ordinance to test a centralized inspection program on three lakes. Local lake associations, with partial funding using Legacy Amendment revenue, partnered with the Wright County SWCD, volunteering thousands of hours and tens of thousands of dollars in matching funds. Annandale donated a site for the inspection station. Wait times last year were about 30 seconds.

This year the county hoped to pilot a program on nine lakes within a 15-mile radius. The county folks have invited some of the local angling groups to work with them to create a self-inspection process for those that use the lakes repeatedly over the summer.

Some have complained that this program provides no exit inspection, since some of the lakes are already infested, but this is a straw-man argument. Minnesota provides very little exit inspection on any of our infested lakes, because of the costs involved. The point of the Wright County model is to interrupt the vector of spread, to find that rare infested watercraft or water-related equipment, then clean it. The deeper gripe is likely inconvenience — with inconvenience seen as a barrier to access.

The Wright County Pilot required a DNR permit. On April 5, the DNR sent a letter to the Wright County Board approving the pilot for the three original lakes but denying the expansion to six more lakes. The problem is that without economies of scale, the project is unaffordable. However, the Senate Environment and Natural Resources Funding omnibus bill does contain language to advance the Wright pilot and may save the planned expansion by the end of the legislative session.

If we value access to the utility of our recreational resources, we may have to endure a measure of inconvenience while we look for those needles in a haystack — those few dozen boats and pieces of aquatic equipment each year that transport enough live mussels, plant fragments, snails and so forth to infest a new waterbody.

How much inconvenience is too much? State statutes dictate that efforts to inspect and decontaminate watercraft cannot unduly restrict access, and the DNR has offered a rule-of-thumb limit of 15 minutes. By using good traffic data, it would be possible to create a network of centralized inspection stations and provide protection with a minimum of disruption. We just need to meet people where they already are — near bait and gas stores, where highways intersect. In places where centralized inspection does not make sense, we can use self-inspection programs.

Life is busy. To access our lakes most of us have to rush home, load up groceries, drinks, bait, gear, kids, dogs. We have to get gas, get on the road, get through traffic. AIS inspection would create yet another barrier, another chore before we can get on the water.

To my mind, though, fishing, boating and paddling are about not being in a rush. They are about getting away from that pressure, abandoning that timetable.

When I was a child in Chicago, we would travel to my mother’s cabin in northern Minnesota. It had no electricity, a lake water system and an outhouse. My mother had only two rules at the cabin. First, watch your cigarettes if you smoked. And when you arrived at the kitchen door, she confiscated all watches.

“How will we know when it’s time to eat?” one guest asked. My mother said: “We eat when we’re hungry, drink when we’re dry, and fish in between.”

Time spent ensuring that we protect real access to our natural resources is not only a wise investment but part of the state of mind we’re after when we seek out those resources in the first place. That sense of “getting away from the rat race” is actually the resource we most need to invest in and protect. And that might mean taking a bit of time before launch to ensure that “access” is not impaired by zebra mussels, spiny waterflea or starry stonewort.

Jeff Forester is executive director of Minnesota Lakes and Rivers Advocates www.mnlakesandrivers.org