Moorhead, Minn.

Antibiotics used in medicine are accumulating in the bottom of Minnesota lakes.

That’s the finding of a new study in which a group of scienticts examined decades of sediment pulled from the bottom of lakes.

Why’s it matter? Persistent low doses of antibiotics can lead to bacteria that are resistant to antibiotic treatment. The World Health Organization says currently antibiotic resistance is one of the greatest threats to human health and food security.

Previous studies found antibiotics are common in the water of lakes and streams. But University of Minnesota professor Bill Arnold, said scientists wanted to know how long those drugs remain in lakes.

They looked for 19 antibiotics in the sediment of Lake Pepin, Lake Winona and the Duluth harbor — all of which get water from sewage treatment plants.

Ten of the antibiotics were consistently found at low levels, Arnold said.

“It’s clear the drugs we’re taking — or worse off, disposing of down the toilet, which you shouldn’t do — certainly wind up in lakes,” he said. “And it’s not just that they’re in the river or the lake for a short time what the wastewater is discharged and rapidly disapate, they’re actually making it in to the sediment and persisting.”

- The Water Main: Making sense of the complex world of water

The most persistent drugs found in the sampled lakes are synthetic antibiotics. The antibiotics made through natural processes were found less often. Arnold said that likely means natural drugs break down more readily than synthetic versions.

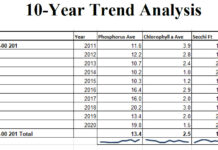

By dating the lake bottom sediments, the scientists found antibiotics all the way back to the 1950s.

“We see things correspond pretty closely to when those drugs were introduced to the market,” Arnold said. “So that tells us that when we introduce new compounds to the market, we can expect to see them start to accumulate in sediments.”

Antibiotics are used more widely in agriculture than for human treatments, but the lake samples showed little evidence of the drugs used to treat farm animals.

“We can’t say for example that agriculture antibiotics are not getting in to the environment. They most certainly are,” Arnold said. “We probably just didn’t look in the right place for them.”

Farm animal waste is usually applied to land, Arnold said, so it’s likely most of the antibiotics bind to soil and aren’t washed into lakes and streams.

Scientists are now doing DNA analysis to see if there is a connection between antibiotics in the lake sediments and the development of resistant bacteria.

Arnold said they also hope to develop a predictive model that could help determine where antibiotic resistant hot spots are most likely to develop in the environment.