Over the past few years, studies of Minnesota’s waters have found a variety of unregulated chemicals — such as pharmaceuticals, fragrances, fire retardants, detergents and insecticides — which are widespread in the state’s lakes and rivers.

His reason: to study an egg yolk protein found in the perchs’ livers, called vitellogenin, which may provide evidence of endocrine disruption in the state’s aquatic species.

Over the past few years, studies of Minnesota’s waters have found a variety of unregulated chemicals — such as pharmaceuticals, fragrances, fire retardants, detergents and insecticides — which are widespread in the state’s lakes and rivers.

Some of these contaminants are called endocrine active chemicals, which can mimic the effects of hormones in humans and wildlife.

These EACs may not exhibit acute toxicity at the levels normally found in the environment, but instead, negatively affect the normal functioning, growth, and reproduction of an organism at very low concentrations, a report from the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency said.

Their presence in Minnesota waters, as well as their potential negative effects on aquatic species, is a growing environmental concern that has continued to show up on Isaacson’s radar over the years.

“What they do is they disrupt the normal cell signaling pathways,” Isaacson said. “They can affect development, so what your baby turns out to look like. They can affect reproduction, so whether or not you can have a child. They can affect your neurology, so how your brain works.”

In the case of Isaacson’s perch — and other species of fish — higher concentrations of vitellogenin are typically found in females because it is a necessary component in egg production; yet for male fish, vitellogenin concentrations are usually low.

However, when male fish are exposed to EACs, they can start to develop female attributes, such as increased vitellogenin concentrations.

In more extreme instances, male fish have also been found to produce eggs in their testes — a condition termed intersex. The exact cause of this isn’t fully known, but it has been linked to certain known endocrine disruptors, such as the plasticizer bisphenol A (BPA) and the herbicide atrazine.

Some species of fish are naturally hermaphroditic and have both male and female sex organs; but, when fish are unnaturally intersex, it can cause reproductive problems within a species.

Typically, the most apparent cases of endocrine disruption among aquatic species are found in bodies of water that are near cities with large populations of people, Isaacson said.

Yet even in northern Minnesota, society’s chemical footprint is far-reaching.

Local impacts

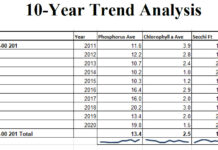

Although he admitted that data is limited (the perch study hasn’t been conducted for enough years), Isaacson and his class have found evidence to support that endocrine disruption may be taking place in nearby Lake Bemidji.

“One thing that we’ve noticed — we don’t have a lot of data — but one thing that’s starting to emerge is that the male fish in Lake Bemidji have higher vitellogenin levels, relative to females, than in other lakes in the area,” Isaacson said.

Another part of Isaacson’s perch study looks at how vitellogenin concentrations may increase in male fish that are found downstream of human wastewater inputs.

“For Bemidji, it’s just what we flush down the drain,” Isaacson said.

According to the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, sources of these particular chemicals to surface water include municipal wastewater discharges, septic systems, runoff from animal agriculture, storm water and even rain and snow.

Isaacson said wastewater treatment plants are not designed to remove EACs; they are designed to remove nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus.

Once wastewater is treated, it is released back into local waterways where it’s used again for any number of purposes, such as supplying drinking water, irrigating crops and sustaining aquatic life, a report from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency said.

When asked what noticeable effects EACs in wastewater can have on fish populations, Isaacson cited a study conducted by the U.S. Geological Survey and University of Colorado scientists in Boulder Creek, Colo.

The study found that the population of fish downstream of the wastewater discharge from a sewage treatment plant was dominated by females, and 18-22% of fish exhibited intersex.

However, Isaacson noted that more research is needed to determine an effective way of removing EACs from wastewater at treatment plants in the U.S.

The Bemidji Wastewater Treatment Facility currently utilizes ultraviolet disinfection during the ice free season, and Isaacson said he is interested in conducting a study looking at how this process could potentially remove EACs from wastewater.

“There have been studies showing that they do break down in the presence of UV light,” Isaacson said. “So we want to look at the concentration of these endocrine active compounds when disinfection is taking place and when disinfection is not taking place to see if there’s a difference.”

Isaacson also noted that human exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals is often a daily occurrence. They can be found in our food and water, household items and that “new car smell.”

And while these chemicals have been linked to health problems such as infertility and different types of cancer, “it’s too soon to say whether feminized fish are indicative of health effects for humans too,” an article by National Geographic said.

Still, Isaacson insisted that it’s necessary to be mindful of everyday products and consider their ramifications on both human health and that of the earth.

“One takeaway is just to be conscious of what you’re consuming. Do you really need to consume whatever product it is?” Isaacson said. “The products that you use in your daily life don’t just affect you, they also affect the environment.”