Now, the infamous invasive plant is finally getting under control.

Authorities with the Pelican River Watershed District are calling it “a big success story”: a multi-year, multi-partner research project on flowering rush yielded some real results, leading to the development of a groundbreaking chemical treatment strategy — and it’s working.

Almost 100 acres of flowering rush have been wiped out from local lakes since the first test treatments began in 2013, and once-dense plant populations that made waters impassable have been thinned enough that boats can now get through without trouble.

The pretty-yet-widely-despised plant is far from eradicated — and never will be entirely — but broad swaths of it that once crippled shoreline activity around parts of Big Detroit and Little Detroit lakes as well as Curfman, Sallie and Melissa lakes, have all but disappeared. Shoreland areas once stagnated by thick growth both above and below the water are now enlivened with boaters and swimmers again.

The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources describes flowering rush as a recreational, economic and ecological threat. The invasive perennial overtakes habitat and outcompetes native aquatic plants, and deprives fish and animals of shelter, food and nesting habitat.

“It actually changes the ecology of a lake,” said Brent Alcott, assistant administrator for the Pelican River Watershed District. “Everything coagulates and collects… it becomes more of a wetland.”

Several years ago, there were lakeshore property owners who sold their homes, Alcott said, because their properties were so adversely affected and they couldn’t access the lake at all anymore.

Those kinds of conditions are changing. What Alcott and others involved in the recent treatment efforts have seen is a rapid return of the lakes’ previous state, pre-infestation. Soon after a population of flowering rush is controlled, the murky water it had infested becomes clearer again. Lily pads that had gotten choked out reappear, and fish that had abandoned the area come back.

The treatment plan now in place in Detroit Lakes calls for once- or twice-yearly applications of the aquatic herbicide diquat, at specific times of the summer and with the chemical injected into the water so it affects the whole plant.

A southward view of Lake Sallie, where the Pelican River flows in, shows a flowering rush infestation, pre-treatment in August 2017. Pelican River Watershed District photo

It’s a unique plan that Detroit Lakes helped to develop and was the first to try. More importantly, it’s the first plan to show real promise in the long-term management of flowering rush. As such, it’s getting a lot of attention.

Tera Guetter, district administrator for the watershed district, said the plan has become a model for other communities struggling with flowering rush. Their local office has consulted with aquatic invasives authorities from the metro area of Minnesota as well as parts of Michigan and Canada. Two academic papers about the local treatment plan have already been published, and another is in the works.

“We’re making worldwide news here,” Guetter said. “We were part of that cutting-edge push (for more aquatic invasive species research) … And our whole project, people are starting to replicate it, how we attacked it.”

‘We couldn’t take it anymore’

Flowering rush was unintentionally introduced in the U.S. in 1897, according to the Minnesota DNR, when cargo ships from Europe and Western Asia discharged contaminated ballast water into the Great Lakes. The plant was discovered in Minnesota in 1968, and in the Detroit Lakes area in 1976, where it was first found in Curfman Lake.

Because of its attractive pink petals, flowering rush was commonly imported in the early days, and sold by the water garden trade. Today, it’s a prohibited invasive species, meaning it’s against the law to possess, import, purchase, transport or introduce it without a proper permit.

Because the plant spreads from its rhizome (an underground stem that sends out roots and shoots in the form of small bulbs, like a lily plant), it cannot be controlled from the parts that stick out above the water. Its underground stems must be destroyed.

“They spread by the root structure, and each little piece you break off can become a new plant,” Guetter said. That’s why early attempts to simply harvest the plants out of the water did not produce permanent results: “It just kept growing and growing. We weren’t getting anywhere.”

With no other proven treatment methods to turn to, those harvesting efforts continued from the time flowering rush was first discovered in Curfman Lake into the early 2000s. During those decades, mechanical harvesters were used to reduce plant density and give boaters an open path to pass through, but the plants continued to grow and spread.

That same view of Lake Sallie, post-treatment in July 2018, shows a drastic reduction in the sprawl and density of the flowering rush. Pelican River Watershed District photo

By the mid-1990s, flowering rush had spread to six other lakes connected to Curfman: Big and Little Detroit, Sallie, Melissa, Muskrat and Mill Pond.

Chemical treatment options were considered, and the effectiveness of different chemicals was tested and studied. One chemical, Imazapyr, raised hopes of success at first, but after three years of little progress, it became clear it wasn’t working well enough.

Detroit Lakes business owners, lakeshore property owners and others grew increasingly concerned about the invasive plant’s impacts on the local economy, ecology and recreational opportunities, and in 2008, a citizen movement called “Crush the Rush” was formed. It was at this time that the Pelican River Watershed District started actively seeking some outside help to try and find a solution.

“We couldn’t take it anymore,” Guetter said.

Since flowering rush was a problem no one had yet solved, Guetter found John Madsen, a plant and soil sciences professor at Mississippi State University. Madsen turned out to be instrumental in the flowering rush study and subsequent treatment plan, and that plan would ultimately become a game-changer in the world of flowering rush management.

Early research and testing efforts expanded to include a complex network of additional researchers, chemical treatment contractors, local lake associations, the DNR, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and other stakeholders — and those efforts did not come cheap. Research work and test treatments conducted between 2010 and 2016 alone cost $750,000. About $450,000 of that came from local funds and the rest from state and federal grants.

‘It’s working’

The study included the collection of thousands of plant samples for analysis, which were test-treated with various chemicals first in the lab, and then later on local lakes, on 10-acre test plots. Researchers studied the plants’ responses to each chemical, as well as their growth and reproductive cycles.

They discovered the effectiveness of diquat through these efforts, and also learned that the chemical needed to be injected into the water to really get at the roots of the plant.

“Contact herbicides were only killing the stuff on top, like giving it a haircut,” Alcott explained. “Really injecting it into the water gets the whole plant … effectively killing it.”

Multiple applications of diquat are also crucial to the process. Alcott said flowering rush will regrow itself over and over again using stored-up energy, so that energy must be completely depleted in order to prevent regrowth. Killing the plant multiple times uses up those energy stores.

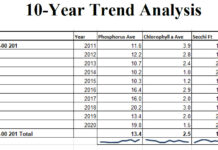

The method has made a big difference. Between 2013 and 2019, Big Detroit and Little Detroit lakes, along with Curfman Lake, have seen a combined 70-plus acre reduction in infested waters, with 102 acres treated for flowering rush in 2019, down from 172 at its peak in 2013. Importantly, the acres that continue to be treated are now far less dense than they once were, so the flowering rush is much less intrusive.

Similarly, flowering rush infestation on Lake Melissa has dropped from 59 acres in 2013 to 39 acres today — again, with those existing acres being far less dense.

“It’s been a lot of work,” Guetter said. “It’s been a long haul, but it’s a big success story.”